From Gap to Growth in Development Finance: Leveraging Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) to Bridge the Infrastructure Financing Gap

Source: Claudio Saraceno.

By Sera Yun

I. Introduction

With only six years left until the deadline of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, new figures released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) indicate that between $5.4 - 6.4 trillion is needed annually to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[1] However, the international development community and countries face a growing need to navigate the challenges brought forth by de-globalization.

De-globalization—in the context of global development finance—refers to a movement toward reduced economic integration and interdependencies, decreased reliance on international trade and investments, and heightened geopolitical tensions that induce a shift away from multilateral cooperation in addressing development financing challenges.[2] Its effects manifest as increased financial and economic volatility, retreat in cross-border capital mobility, reductions in foreign investments, global supply chain disruptions, and re-orientation of funding and policy priorities.[3] Together, these headwinds are anticipated to pose real challenges to development financing allocation and opportunities.[4]

In particular, this signifies far-reaching implications for the funding of infrastructure development, which represents an essential building block for economic growth and competitiveness. Robust and sound infrastructure is vital for countries to respond to emerging challenges, such as climate change, technology disruptions, and pandemics.[5] For these reasons, increased financing and investments in infrastructure have been emphasized in the context of sustainable development, with particular attention to addressing the infrastructure financing gap.

II. Understanding the Infrastructure Financing Gap

Figure 1. Global Infrastructure Financing Gap between Current Trends and Investment Need (2010-2040)

Figure 2. Global Investment Needs by Income Group (% of GDP). Source: Recreated by the author with data from the Global Infrastructure Outlook [6]

The infrastructure financing gap refers to the disparity between the demand for infrastructure investment and the available funding.[7] The G20’s Infrastructure Initiative projects a global infrastructure financing gap of $15 trillion through 2040, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) falling the furthest behind.[8] Failure to address this gap can have profound implications for economic development, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability.[9] However, public financing alone will be insufficient to meet these demands. Reflecting this reality, innovative financing mechanisms have sprung up to accelerate private sector involvement, with hopes of mobilizing additional resources for infrastructure development projects, such as social impact and green bonds, credit enhancement mechanisms, blended finance, and risk mitigation instruments.[10]

III. Role of Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastructure Development

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) have emerged as a valuable tool for financing infrastructure projects, effectively leveraging the complementary strengths of the public and private sectors. Unlike traditional public procurement models—which rely solely on public sector funding and expertise—PPPs involve collaboration between government agencies and private sector entities throughout the project lifecycle.[11]

PPPs present particular benefits for infrastructure projects by: 1) ensuring financial sustainability, 2) fostering innovation, and 3) enhancing sustainable development. First, when accompanied by effective project structuring and rigorous financial analysis, PPPs increase the pool of resources to meet the large costs of infrastructure development by mobilizing private investment alongside public funds.[12] Furthermore, by ensuring that projects are economically viable and capable of generating sufficient returns, PPPs can enhance debt sustainability and lessen the strain on public budgets. Second, PPPs foster innovation by leveraging the expertise and technology of the private sector through strategic partnerships, resulting in more efficient and effective delivery of infrastructure projects and services. Third, PPPs facilitate investments in projects with positive social and environmental impacts, aligning public and private sector interests to contribute to sustainable development objectives.[15] This is especially important for large-scale infrastructure projects (e.g., railways, ports, power plants) with a lasting impact on people and communities. For example, by deliberately structuring projects to involve climate-smart approaches or mainstreaming the reach of development gains for underserved communities, PPPs can promote climate resilience and socioeconomic inclusion, thereby achieving sustainable development and growth.[16] [17]

Financial commitments to PPPs for infrastructure in LMICs increased steadily from 2003 to 2019, but declined sharply in 2020 with the outbreak of COVID-19.[18] Although data for 2023 remains inconclusive at this time, financing recovered to nearly pre-pandemic levels in 2022. Over the last two decades, the average annual commitment amounted to $82.8 billion with a cumulative total of $1.7 trillion, distributed across various parts of the developing world.[19]

Figure 3. Financial Commitments to PPPs for Infrastructure in LMICs (2003-2023)

Figure 4. Cumulative Financial Commitments to PPPs for Infrastructure in LMICs (2003-2023). Source: Recreated by the author with data from the World Bank [20]

IV. Risk-Sharing Mechanisms of PPPs through the Lens of De-Globalization

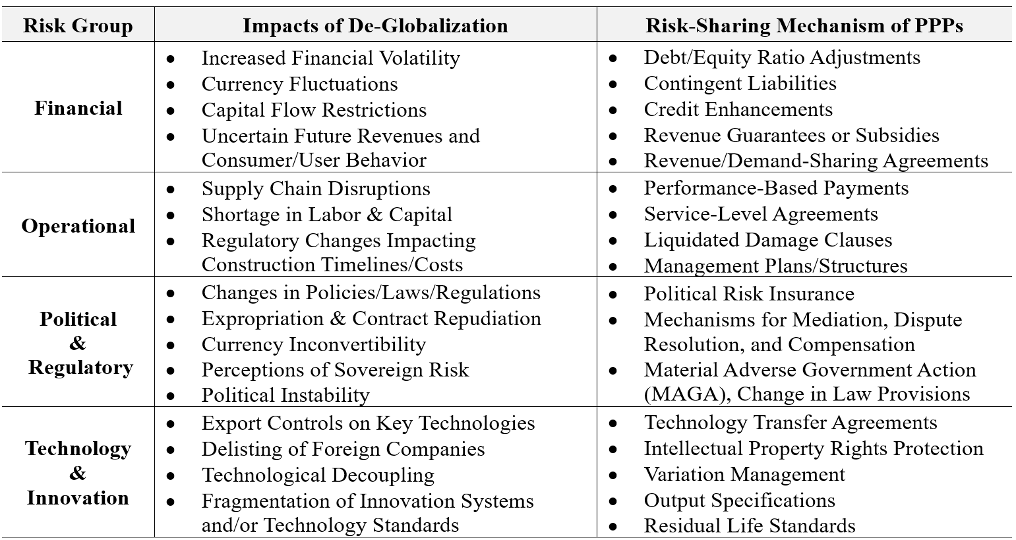

Notwithstanding the well-tested benefits of PPPs, their positive attributes are not necessarily new in the realm of international development. Nonetheless, in a world of increasing de-globalization, PPPs offer a distinct advantage through their innovative ‘risk-sharing’ mechanisms. They can provide robust measures to address risks that may arise at various stages of infrastructure projects, which this article will categorize into the following four groups: 1) Financial Risks, 2) Operational Risks, 3) Political & Regulatory Risks, and 4) Technology & Innovation Risks.

Financial Risks

A prominent characteristic of PPPs is their ability to distribute financial risks between the public and private sectors. Specific mechanisms include debt/equity ratio adjustments, credit enhancements, and contingent liabilities to enhance the financial viability of projects.[21] [22] This is particularly important as investment decisions and project financing capacities can be seriously affected by increased financial volatility, currency fluctuations, and capital flow restrictions in the context of de-globalization. Such risk-sharing measures can diversify funding sources, align financial incentives between the public and private partners, and enhance fiscal resilience and ‘value for money’ in infrastructure projects amid changes in the global financial landscape.

Another risk associated with de-globalization is the rise of trade barriers and protectionism, which can exacerbate uncertainties regarding future revenues and user behavior. This is especially relevant for projects that are closely tied to the provision of public utilities, goods, and services, which are susceptible to changing demands and preferences in consumption (e.g., electricity, telecommunications, transportation). In this light, PPPs allow governments to provide revenue guarantees or subsidies to mitigate the risk of lower-than-expected usage and demand volatility.[23] These risk-sharing mechanisms provide financial safeguards that can support the viability and sustainability of infrastructure projects despite fluctuations in demand or market dynamics.

Operational Risks

Infrastructure projects entail operational risks, which must be allocated between the public and private sectors across the phases of construction, operation, and maintenance. For example, private entities may assume responsibility for operational performance and routine maintenance, while public entities retain oversight and regulatory authority. Under this format, each party bears the costs of their respective activities to ensure the quality and continuity of operations. For this process, specific risk-sharing mechanisms include performance-based payments, service-level agreements, liquidated damages clauses, and clear management plans/structures.[24] In the context of de-globalization, these measures are pertinent to articulating and negotiating which parties are primarily responsible for hedging against and planning for unexpected supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and regulatory changes.[25] By providing room for a clear allocation and delineation of duties, PPPs can incentivize the efficient delivery of operational and performance targets, minimize cost overruns, and ensure the timely completion of infrastructure projects.

Political & Regulatory Risks

De-globalization may heighten geopolitical tensions and restrictions on economic openness, resulting in policy and regulatory uncertainties that closely intersect with project implementation, financing, and operation. For infrastructure development, problems may arise in the form of expropriation, currency inconvertibility, non-renewal of licenses, and contract repudiation.[26] In PPPs, such risks may be absorbed or managed through the inclusion of political risk insurance, robust procurement and permit processes, provisions for change in law or Material Adverse Government Action (MAGA), and mechanisms for mediation, dispute resolution, and compensation.[27] In this way, these partnerships can provide relevant safeguards and create more manageable risk profiles for greater stability and predictability during the project lifecycle—vital for boosting private sector investment and participation.[28]

This poses important implications for countries with infrastructure development needs across all income groups. For upper-middle-income countries, de-globalization may lead to divergent regulatory frameworks and standards, increasing the complexity and costs of compliance in infrastructure projects.[29] For LMICs, de-globalization may add to the perception of sovereign risk, political instability, and government intervention, which can severely reduce the availability and supply of capital. In this light, PPPs present opportunities to diversify risk exposure across multiple parties in increasingly volatile political and regulatory environments.

Technology & Innovation Risks

PPPs have an important role in the adoption of advanced technology and innovation, serving as vital instruments to enhance sustainable solutions in infrastructure projects. Specific measures include technology transfer agreements, protection clauses for intellectual property rights, variation management, output specifications, and residual life standards.[30] These measures are essential in preventing technology obsolescence and maintaining long-term technological viability for the public sector. At the same time, ensuring the secure transfer of proprietary technology and data without leakage is critical for the private sector.[31]

This touches upon important implications of de-globalization, which may intensify export controls on key technologies, delisting of foreign companies, technological decoupling, and fragmentation of innovation systems and technology standards.[32][33] Such factors can affect the sourcing, adoption, and integration of technology solutions into infrastructure projects.[34] In this regard, PPPs can facilitate the secure transfer of technology where the forces of de-globalization might otherwise hinder adoption, particularly for projects that rely on advanced technologies and complex technical requirements (e.g., energy, transportation, ICT). Thus, these risk-sharing mechanisms enable technology-intensive infrastructure projects to not only meet investors’ demands for quality and reliability but also to remain competitive and resilient in the face of disruptive technologies and external uncertainties.

Table 1. Summary of Risk Group, Impacts of De-Globalization, and Risk-Sharing Mechanisms of PPPs. Source: Created by the author.

As such, in addressing the uncertainties and distinct challenges of de-globalization, PPPs offer a wide menu of risk-sharing mechanisms for project planning, development, and execution. By optimizing resource allocation and risk-sharing based on each party’s ability to manage and mitigate those risks effectively, PPPs can enhance the resilience, sustainability, and success of infrastructure projects in the face of evolving global dynamics.

V. Best Practices in Leveraging the Risk-Sharing Mechanisms of PPPs in Infrastructure: Cebu-Cordova Link Expressway (Philippines, 2018-2022)

This section briefly examines the case of the Cebu-Cordova Link Expressway in the Philippines, which exemplifies how the risk-sharing mechanisms of PPPs can be utilized in practice at various stages of an infrastructure development project.

With the objective of improving transportation infrastructure and connectivity in the Philippines, the Cebu-Cordova Link Expressway project was carried out by a partnership comprising the local government units of Cebu and Cordova, Metro Pacific Tollways Corporation (MPTC), Cebu Cordova Link Expressway Corporation (CCLEC), and a joint venture of international infrastructure firms (First Balfour and DM Consunji Inc. of the Philippines and Acciona Construccion S.A. of Spain).[35] [36]

Under the project’s concession agreement, CCLEC assumed authority for the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of the expressway, while local governments undertook the monitoring, inspection, and evaluation—in line with operational targets and performance metrics in traffic volume, safety, and service quality.[37] Contractual arrangements further included provisions that delegated to Cebu and Cordova the facilitation of right-of-way issues by allowing the possession and use of land for CCLEC. This eventually served as the legal basis for securing critical support from the local governments in authorizing the use of city-owned lots.[38]

To address the large size of the project and its financial risks, MPTC financed a portion of the project through equity investments and secured a syndicated loan of PHP19 billion ($330 million) from a consortium of six local banks.[39] Local governments agreed to revenue-sharing provisions in place of upfront payments or concession fees, with the intent to lessen the financing burden for the private sector and bolster the project’s bankability.[40] This positioning proved crucial later when the private sector managed to extend the concessional period and adjust toll fees in response to an unexpected cost overrun of PHP5 billion ($87 million) from COVID-19 and a typhoon.[41] [42]

To this end, the project successfully implemented the technology, expertise, and innovation from international partners—particularly in bridge design, traffic safety, resilience against natural hazards, and advanced toll collection systems.[43] Additionally, to safeguard the expressway’s long-term functionality and durability until the end of the concessional period, the agreement included provisions for its preservation and maintenance, adhering to prudent industry practices and residual life standards.[44]

Since its official inauguration in April 2022, the expressway has served 3.6 million vehicles and generates at least PHP1.4 million ($24,000) daily.[45] In its first year, each local government received PHP1.69 million ($30,000) as a share of the toll revenues.[46] As Cebu’s iconic landmark, as well as the longest and tallest bridge in the Philippines, the expressway is already undertaking projects for road extensions and the development of surrounding infrastructure. These initiatives are expected to further accelerate investments, business opportunities, and the region’s socioeconomic recovery.[47]

The exemplary case of the Cebu-Cordova Link Expressway in the Philippines highlights the versatility and effectiveness of the unique risk-sharing mechanisms of PPPs. By distributing risks and harnessing the private sector, PPPs offer a viable pathway to overcome the funding constraints, regulatory hurdles, and governance issues that are expected to be more prominent in a de-globalizing world, while also driving transformational infrastructure that can unlock socioeconomic development and growth.

VI. Challenges & Way Forward: The Role of Development Finance Institutions

Despite their benefits, PPPs should not be viewed as a panacea for infrastructure financing in response to the complex challenges of de-globalization. At this juncture, development finance institutions (DFIs) have a unique role to play as a linkage across public and private sector partners by creating a more enabling ecosystem for PPPs. The following describes a number of clear, specific, and actionable recommendations.

First, as financiers of sustainable development and economies, DFIs can directly enhance the financial viability and bankability of PPP-led infrastructure projects. Specifically, they can provide concessional financing (e.g., viability gap funding), credit enhancement mechanisms (e.g., mezzanine financing, financial intermediary loans), risk mitigation instruments (e.g., partial credit guarantees, political risk insurance, liquidity facilities), and dedicated funds for the maintenance and rehabilitation of PPP-led infrastructure.[48] However, these financing tools should not be stand-alone. They are better when accompanied by adequate technical assistance, capacity-building, and policy advice for project stakeholders across the overarching lifecycle of PPPs. For example, knowledge exchange programs, peer-learning platforms, and tailored consultations allow DFIs to facilitate systematic learning and guidance with respect to market assessments, country diagnostics, project structuring, investment strategy, and financial risk modeling, among others.[49]

Second, to address the complexities in legal, contractual, and procurement processes—that often stand as persistent barriers in PPPs—DFIs must continue to provide tailored guidelines, toolkits, and frameworks to expedite the streamlining and standardization processes. The PPP Advisory Services of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) of the World Bank, for example, offer a diverse array of knowledge products and legal resources—including certifications, contractual and legislative provisions, sample clauses, and dispute resolution checklists—for project stakeholders to utilize and benchmark. As such, DFIs can provide critical advisory services to transfer lessons learned and guide the replication of “stress-tested” best practices and international standards.

Third, as carriers of global convening power, DFIs are well-positioned to leverage their fortes in multi-stakeholder engagement and serve as marketplaces of ideas, knowledge, and strategic partnerships. This can catalyze stable and predictable investment climates through policy dialogue and facilitate collaboration between the private and public sectors to sustain the positive spillover and transfer of knowledge, technologies, and innovations. The Global PPP Community Forum of the World Bank and the PPP Knowledge Lab (launched by Multilateral Development Banks and PPIAF) serve as working examples of this support. In the long run, efforts can be enhanced to support governments in strengthening their legal, institutional, and governance structures to not only ensure resilience against external shocks but also to bolster transparency and accountability.

VII. Conclusion

In strategically adapting to the challenges and risks presented by a de-globalizing world, PPPs represent a powerful tool to enhance the financial sustainability, operational efficiency, and sustainable development outcomes of infrastructure projects. It is also important to note that well-connected and sound infrastructure can mitigate and absorb the impacts of de-globalization, thus offering the potential to form a positive feedback loop. Moving forward, while PPPs hold tremendous promise, more proactive and concerted efforts from DFIs will be the linchpin. By diversifying, innovating, and guiding the unique risk-sharing mechanisms of PPPs, DFIs must be at the forefront of transforming current challenges into future opportunities and furthering the full potential of PPPs to bridge the infrastructure financing gap and, at large, serve as a vehicle for sustainable development.

About the author

Sera Yun is a Trust Fund Management Consultant at the Grants & Co-Financing Management (GCM) Unit of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Prior to this role, she has previously worked at the World Bank (Korea Green Growth Trust Fund and the Infrastructure Chief Economist’s Office), the National Institute of Green Technology of the Republic of Korea, and the UNDP Policy Centre. She holds a Master’s Degree in International Commerce and Development Finance from Seoul National University, Graduate School of International Studies.

Endnotes

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “UNCTAD Counts the Costs of Achieving Sustainable Development Goals.” September 18, 2023. https://unctad.org/news/unctad-counts-costs-achieving-sustainable-development-goals.

Mallaby, Sebastian. “Globalization Resets.” International Monetary Fund, December 16, 2023. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/12/mallaby.htm.

International Monetary Fund. “Geo-Economic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism.” January 15, 2023. https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/006/2023/001/article-A001-en.xml.

Laxton, Valerie, and Nancy Lee. “MDBs Need Major Reforms, Not Just More Funding, to Address Climate and Development Finance Challenges.” World Resources Institute, July 6, 2023. https://www.wri.org/technical-perspectives/mdb-reform-climate-sustainable-development.

Global Infrastructure Hub. “The Vital Role of Infrastructure in Economic Growth and Development.” November 19, 2021. https://www.gihub.org/articles/the-vital-role-of-infrastructure-in-economic-growth-and-development/.

Ibid.

Global Infrastructure Hub. “Global Infrastructure Outlook.” September 4, 2017.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Familiar, Jorge. “Innovative Financing Solutions Can Meet Both Old and New Challenges.” World Bank, June 1, 2023. https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/innovative-financing-solutions-can-meet-both-old-and-new-challenge.

Beckers, Frank, and Uwe Stegemann. “A Smarter Way to Think about Public–Private Partnerships.” McKinsey & Company, September 10, 2021. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/a-smarter-way-to-think-about-public-private-partnerships.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Mohieldin, Mahmoud. “SDGs and PPPs: What’s the Connection?” World Bank, April 12, 2018. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/sdgs-and-ppps-whats-connection.

Foerster, Susanne, and Jenny Chao. “Leveraging PPPs to Tackle Climate Change – A New Resource.” World Bank, May 26, 2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/leveraging-ppps-tackle-climate-change-new-resource.

Nyirinkindi, Emmanuel. “Five Ways PPPs Deliver Impact.” World Bank, November 30, 2023. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/five-ways-ppps-deliver-impact.

World Bank. “Latest Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPPI) Database: Half-Year (H1) Update, 2023.” https://ppi.worldbank.org/en/ppidata.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Debt/equity ratio adjustments refer to the combination of debt and equity in raising project financing and tailoring their ratio according to the expected flow of funds, revenues, and expenditures; credit enhancements refer to risk transfer strategies wherein the provider, for a fee, agrees to compensate its lenders in the event of default or loss due to certain circumstances; contingent liabilities refer to payment commitments whose occurrence, timing, and magnitude are made contingent on future events and are used to allow parties to legally back out of investments if they are not met.

World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank. “Public-Private Partnerships Reference Guide (Version 2.0).” 2014. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/600511468336720455/pdf/903840PPP0Refe0Box385311B000PUBLIC0.pdf.

Ibid.

Ibid.

S&P Global. “The Evolution of Deglobalization.” https://www.spglobal.com/en/enterprise/geopolitical-risk/evolution-of-deglobalization/.

World Economic Forum. “Mitigation of Political & Regulatory Risk in Infrastructure Projects Introduction and Landscape of Risk.” January 2015. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Risk_Mitigation_Report14.pdf.

World Bank. “Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions.” 2017. https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/directions_services/fininfra/News/Guidance_PPP_Contractual_Provisions_EN_2017.pdf.

World Economic Forum. “Mitigation of Political & Regulatory Risk in Infrastructure Projects Introduction and Landscape of Risk.” January 2015. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Risk_Mitigation_Report14.pdf.

Ibid.

World Bank. “PPP Contracts in An Age of Disruption.” September 2022. https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/sites/ppp.worldbank.org/files/2023-10/10028%20-%20PPP%20Contracts%20in%20An%20Age%20of%20Disruption%20%28October%202023%29.pdf.

Ibid.

World Economic Forum. “The Global Risks Report 2023.” 2023. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf.

McFee, Innes. “Technological Decoupling Is the Real Deglobalisation Threat.” Oxford Economics, April 20, 2022. https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Technological-decoupling-is-the-real-deglobalisation-threat.pdf.

World Bank PPP Legal Resource Center (PPPLRC). “Infrastructure PPPs Impacted by Disruptive Technology.” March 30, 2024. https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/infrastructure-ppps-impacted-disruptive-technology.

Metro Pacific Tollways Corporation. “CCLEX Main Bridge Span Now Connected.” October 5, 2021. https://www.mptc.com.ph/index.php/2021/10/05/cclex-main-bridge-span-now-connected/.

MTPC is the national toll road operator of the Philippines and CCLEC is a subsidiary of MPTC and the main contractor of this PPP.

Metro Pacific Tollways Corporation and Subsidiaries. “Consolidated Financial Statements (2016-2017) and Independent Auditor’s Report”. February 23, 2018. https://www.mpic.com.ph/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2017-Financial-Statements-1.pdf.

Sun Star. “Third Bridge Contractor Gets to Use City Lot in Ermita.” December 8, 2018. https://www.sunstar.com.ph/cebu/local-news/third-bridge-contractor-gets-to-use-city-lot-in-ermita.

Limpag, Max. “Cebu-Cordova Bridge Done by 2021; CCLEC Signs PHP 19B Loan Agreement.” My Cebu, February 10, 2019. https://www.mycebu.ph/article/cebu-cordova-bridge-done-by-2021/.

Metro Pacific Tollways Corporation and Subsidiaries. “Consolidated Financial Statements (2021-2022) and Independent Auditor’s Report”. April 3, 2023. https://www.mpic.com.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Metro-Pacific-Tollways-Corporation_2022-12-31_PDF-Clients-Copy.pdf.

Ibid.

Letigio, Delta Dyrecka. “MPTC’s Management of CCLEX Extended to 45 Years.” Cebu Daily News, May 25, 2022. https://cebudailynews.inquirer.net/443356/mptcs-management-of-cclex-extended-to-45-years-bmb.

Europa Wire. “Cebu-Cordova Link Expressway Project Earns Global Recognition for Innovation and Excellence.” November 11, 2023. https://news.europawire.eu/cebu-cordova-link-expressway-project-earns-global-recognition-for-innovation-and-excellence/eu-press-release/2023/11/11/13/28/57/124887/.

Metro Pacific Tollways Corporation and Subsidiaries. “Consolidated Financial Statements (2021-2022) and Independent Auditor’s Report”. April 3, 2023. https://www.mpic.com.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Metro-Pacific-Tollways-Corporation_2022-12-31_PDF-Clients-Copy.pdf.

Rosales, Elijah Felice. “CCLEX Sees PHP 2 Million Daily Toll Revenue.” Phil Star Global, September 19, 2022. https://www.philstar.com/business/2022/09/19/2210579/cclex-sees-p2-million-daily-toll-revenue.

Sun Star. “Cebu City, Cordova Get PHP 3.4M Share in CCLEX Toll Revenue.” April 27, 2023. https://www.sunstar.com.ph/cebu/local-news/cebu-city-cordova-get-p34m-share-in-cclex-toll-revenue.

Baclig, Cristina Eloisa. “CCLEX Hastens Post-COVID Growth, Recovery of Central Visayas Region.” Inquirer, July 25, 2022. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1634186/cclex-hastens-post-covid-growth-recovery-of-central-visayas-region-study.

World Bank PPP Legal Resource Center (PPPLRC). “World Bank Group’s Role in PPPs.” https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/world-bank-group-s-role-ppps.

Mohammed, Nadir, Yara Salem, Mikel Ibanez, and Lorenzo Bertolini. “How Can Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) Be Successful?” World Bank, July 6, 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/mena/brief/how-can-public-private-partnerships-ppps-be-successful.

Ibid.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of the editors or the journal.