Growing Out of Debt: A Conversation About the Global Economy

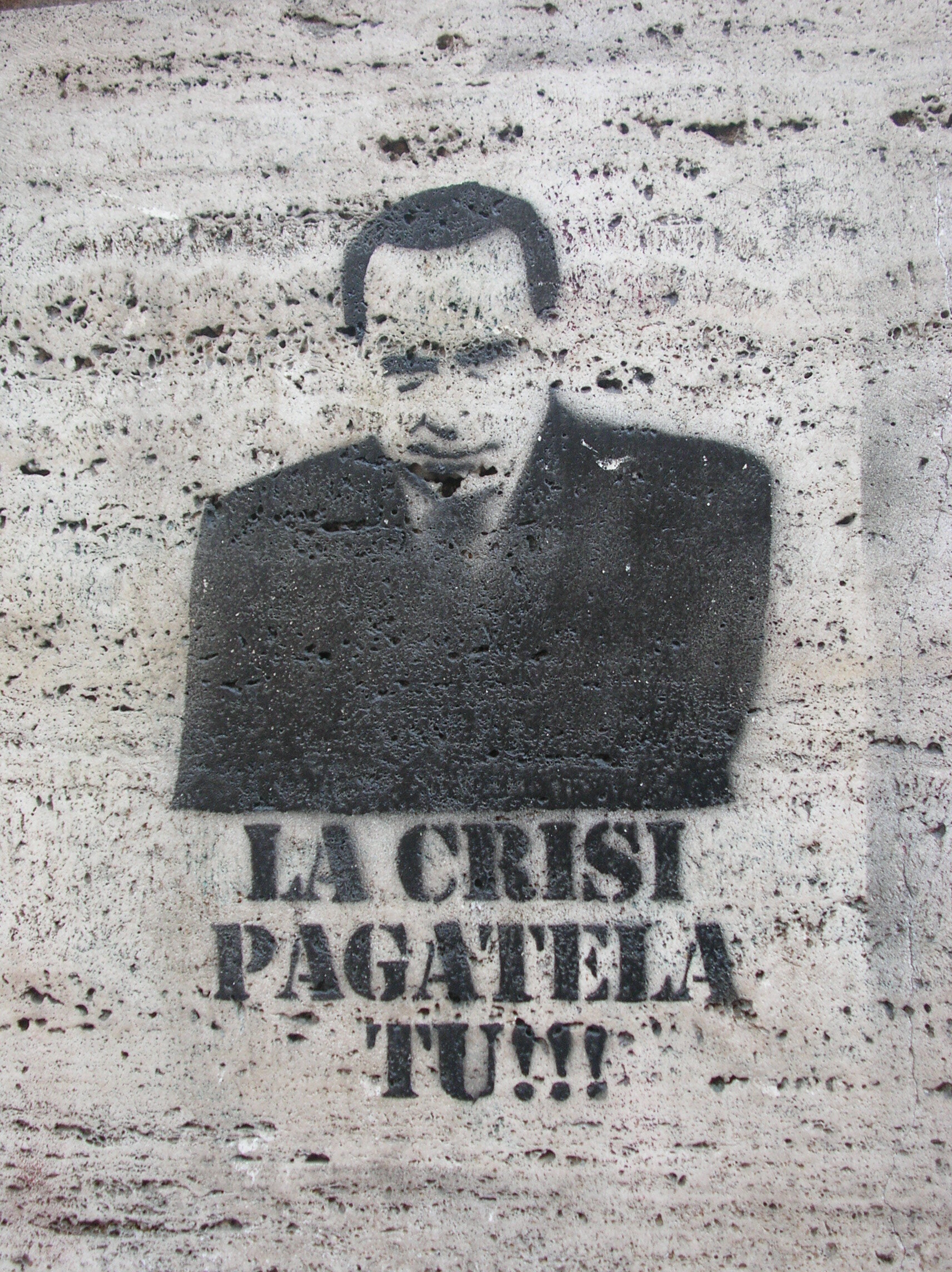

Political gaffiti in via Carducci, Milan, against Silvio Berlusconi and his involvement in the economic crisis. The writing says: "Be you who will pay the crisis"

An Interview with Domingo Cavallo and Rakesh Mohan

YJIA: What lessons have you learned in your roles as central bank chiefs that could help guide handling of the financial crises in the United States and Europe today?

Cavallo: Financial stability should be one of the commitments and goals of central banks—not only price stability but also financial stability. That is even more important than growth and employment as a target of monetary policy because in circumstances of financial crises, only central banks can provide the lending of last resort that is needed to prevent liquidity crises from developing into solvency crises. In my view, in the United States the Fed could cope with the crisis because it acted as a lender of last resort. But in Europe, the ECB [European Central Bank] is not acting as a lender of last resort and therefore it is not finding fast solutions to the crisis.

Mohan: I would emphasize the same point but would add that what follows from this argument of having financial stability as a key objective of central banks is the role of financial regulation and supervision. In most countries, financial regulation and supervision used to be done by the same organization—that is, the central bank. If the central bank is to be responsible for financial stability, then it must have a strong role in financial regulation and supervision. Even if the regulator is a separate organization, the central bank must have some oversight. That way, it can do much more to prevent a crisis by getting real time information about what is happening in the large financial institutions and acting on a real time basis beyond monetary policy.

The principle of lender of last resort is really at issue where there is a liquidity problem but not insolvency. Of course, a liquidity problem can turn into insolvency. And often there is a degree of uncertainty about it. Usually, you have to take action very quickly and for that, the central bank needs to have a strong role in both regulation and supervision.

Cavallo: I agree and would add that whenever an institution, or even a country, becomes insolvent and you realize that that you are dealing not only with a liquidity crisis but an insolvency crisis, the faster the solution mechanisms are put into place, the better. What happened in Europe is that even though everybody recognized that Greece was already insolvent one year ago, they took another year to organize an orderly debt restructuring. The more you delay and the more financing that you provide allows some creditors to bail out of an insolvent country but those that remain lose more and more possibilities of recovery. Once you are convinced that it’s insolvency and not only a liquidity crisis, you should work for very fast resolution mechanisms to allocate the losses and to recreate the conditions of sustainability for whatever debt remains in place.

Mohan: I would again agree with Domingo but would like to add that there is a difference here in terms of what may happen in an emerging market or a developing country and in a mature economy, particularly in Europe. It has to do with future prospects. When you restructure debt, the key is to look at the minimum amount of debt restructuring to make it sustainable.

The problem with Europe is that given the demographics, the prospect for growth is low, which means that they need more debt restructuring because they can’t grow out of their debt. If population growth is zero, then the chances of getting economic growth of more than 2 percent a year are very low, even if all the necessary reforms are carried out. So in that sense, there is an immediate problem of insolvency but there is also a longer problem of sustainability. That probably means that the debt-to-GDP ratio in these countries actually has to be lower than in an emerging market country because they can’t grow out of it.

YJIA: With the recent bond-market run on Italy, in addition to the crisis in Greece, there has been much speculation about the possibility of the breaking up of the euro. What are your thoughts on the economic and political implications of such a development?

Cavallo: I think that would not be a solution for the crisis because if, let’s say, Germany, the most solvent country, decides to exit the Euro, it will face the same problem as Switzerland is facing today. Germany’s currency will become very strong vis-à-vis the currencies of the rest of Europe and that will discourage exports. It will be a way of disintegrating Europe. Chancellor Merkel has committed Germany to maintaining the single currency for all of the Eurozone and I think that this is a smart decision.

Now, the countries in the periphery of Europe that are having problems should be helped in two ways. One, by facilitating mechanisms to put their debts onto a sus- tainable course and, two, by helping them introduce the necessary reforms to increase productivity and competitiveness without abandoning the Euro. If the ECB is a lender of last resort for countries that are suffering a liquidity crisis but are not insolvent—such as Italy and Spain—that will soften the monetary policy of the ECB and will probably weaken the Euro for a while. But some weakening of the euro, in my opinion, would help to cope with the crisis and would be useful to maintain the integrity of the Eurozone.

In that sense, what the European central bank should do is to supply similar policies as the Fed is supplying in the US. When you have two very important monetary areas, and one implements a very expansionary monetary policy like the Fed is doing and the other tries to implement a much stricter monetary policy as is happening in the Eurozone, then the currency of the latter will become too strong. That creates problems, particularly in the European countries that are relatively less competitive, such as Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy.

Mohan: Very clearly the maintenance of the euro is extremely important politically for Europe. The Euro arose because of a perceived political necessity after the experiences of the First and Second World Wars. It was based on the resolve of Europeans not to have another disaster like we had twice in one century. Greater unification in Europe reduces the likelihood of another disaster. So there is much more behind the euro than just the currency. This is both a problem and a strength.

That’s because nothing is forever. To think that there can never be a country leaving the Euro—long-term as opposed to the immediate situation—I think is an issue. Once they get over the current crisis, the Eurozone needs to give some serious thought to the subject of how a country may leave the Euro—or how it may be ejected from the Eurozone. There ought to be some process or procedure behind it. At present, there is no provision in the treaty for this, but it’s one point that people need to think about.

Second, even if there is a unified currency like in the US, there are still lots of differences between regions. But the reason this works in the US as compared to Europe is that there is much greater labor mobility and wage flexibility in the United States, for better or for worse. A European can technically work anywhere he or she wants to in the Union but there are still language issues. India faces a similar problem. We are a huge country and we have all kinds of different languages, and there are also different wage levels among regions.

The third issue has to do with what we might call the central fiscal authority. The Eurozone needs a verification mechanism so that beyond a specified level of sover- eign indebtedness, some agreed-upon European authority has to authorize additional borrowing by member states. And along with that permission would come conditions so that a country can’t get into a situation where you have a 160 percent debt-to-GDP ratio. For example, according to the Indian constitution, a state cannot borrow in the market without the permission of the central government (as long as they still have outstanding debts with the central government). I think that something like that is feasible in Europe.

Cavallo: I think that will actually happen in the next year in Europe. Countries that have to restructure their debts will not get financing from the market for a long period of time which means they will only get financing to cover their remaining fiscal deficits to the extent that they can convince Europe to provide that financing. Therefore, the agency that will provide it will be able to impose some conditionality and the public finances of these countries will then be controlled by Europe. I think eventually what Europe needs is a unified fiscal system but countries that so far have been very responsible such as Germany would also have to resign fiscal sovereignty and that is not very politically palatable in Germany right now. But Greece, Portugal, and Ireland will be obliged to resign some fiscal sovereignty, otherwise they will not gain financing. Merkel recently said that “what we need is more Europe,” that is, more political unification, not only currency unification. To achieve centralized control of public finances, Europe needs to take a step forward in terms of political unification.

Mohan: One of the things that also needs to be observed is the irresponsibility of the private sector in lending to in- debted countries. The market did not distinguish between

the credit rating of Greece and Portugal, on the one side, and the core countries on the other. There was not enough of a spread between the debt of the peripheral and the core countries. This is a clear market failure. The market felt that banks and countries would always be bailed out. I think this issue also has to be addressed.

Cavallo: And risk appraisal is one of the main responsibilities of lenders, of banks. No doubt there was a misappraisal of risk on the side of the lenders and of the banks. That is also the justification for having them suffer some of the losses because they made the mistakes. The question is to find orderly ways of allocating these losses and to prevent the complete collapse of the financial system.

YJIA: To what extent do you believe that politicians in the United States and Europe are gridlocked over difficult political decisions, such as the implementation of austerity measures, because they are not incentivized to pursue policies that consider long-term costs and benefits?

Cavallo: More than austerity measures, what you need in these countries is to recreate conditions for sustainable growth. Austerity may be an ingredient but more important is flexibility and creating conditions for efficient investment. In particular in advanced countries, investing more in research and development and pushing economies by introducing technological changes and technological progress in general is the key for growing out of debts. Austerity is necessary particularly in those countries that have completely lost credit because if you do not implement the fiscal consolidation then you will have to print money to finance those deficits, which generates inflation and of course it brings about the devaluation of the currency.

Mohan: Yes, I think there is a difference between Europe and the US in that the US, in a way, does not have a core economic problem but a political problem—a certain breakdown of dialogue, discussion, and compromise between the two major parties. The US has growth potential based both on its dynamism and all its innovation as well as its open immigration policy, whereas in the case of Europe, there is a long-term problem of stagnation due to demographics.

YJIA: What are your long-term policy prescriptions to boost competitiveness in the advanced economies?

Cavallo: I do not understand why the leadership in the US does not accept the carbon tax, which would encourage research and development of clean energy. The US could be a sort of pioneer in this development and they could sell technology all over the world to induce investment in replacing non-renewable sources of energy with new sources of clean energy. Maybe it is the general opposition to the introduction of any new taxes period, but I think a carbon tax is a very efficient way of internalizing the environmental costs of non-renewable sources of energy. Plus, it would be a very good instrument to make progress in terms of both fiscal consolidation and to promote R&D in clean technologies. That is just an example but I think it’s a very relevant one, particularly in the United States.

Mohan: There are actually a number of things. In Europe, they clearly need a lot of struc- tural reform to make the economies more flexible. But they have a lot of strengths, which they could actually be marketing to the United States. For example, to my recollection, Europe’s per capita energy use is half that of the United States, so they obviously have ways of doing things more efficiently. Second: healthcare. One

of the most striking things is that on average in Europe, the expenditure on health is around 8 percent of GDP. Of course, there are some differences between countries and around 90 percent of that is public expenditure. But in the US, that fig- ure is double at about 16 percent of GDP. What is even more interesting is that the level of US public health expenditure as a proportion of GDP is about the same as in Europe. So in some sense, medicine is as socialized in the United States as in Europe except that it doesn’t do a good job in that people spend as much and more. Yet still the health outcomes are lower than they are in Europe. It is a real puzzle to me why European policymakers and consultants can’t sell technologies and advice to the United States.

YJIA: What are the consequences for developing countries of economic woes and consequent shrinking demand in the US and Europe? How can developing countries insulate themselves from a spread of the crisis?

Cavallo: In the last few years, trade among developing coun- tries has significantly increased particularly since the emergence of China as a big commercial partner. For example, China is now the main export market for South America. India is also important because China and India have exactly the opposite demographic composition of South America. We have relatively low popula- tions with very abundant resources while Asia has the opposite: very large populations and not enough natural resources. So there is a lot of trade already between developing nations themselves.

Of course, developing nations need something else that is very important which comes mainly from advanced economies, and that is technology. I think the comparative advantage of the advanced economies is to push the technological frontier and to be providers of technologies to the world, particularly the large emerging economies.

Mohan: Over the last thirty years, the US was a major importer of goods from Asia. The economic weight of Asia was low so obviously you export to wherever the demand weight is higher. Now there is a fast shifting of weight.

The GDP of the US economy is about $14 trillion, India is one-tenth of that at about $1.4 trillion, and China is one-third at about $4.2 trillion. Given the differences in growth rates over the next ten years, the relative weights between the sizes of these economies will change very quickly, meaning they will trade much more amongst themselves. In fact, over the last ten years or so there have been many more trade pacts among emerging market countries in general.

The US has been sort of a special case, particularly with regards to China. Europe as a whole has not had significant a trade deficit with China—it has been roughly balanced. The US, because of its expansionary fiscal and monetary policy, has been sucking up goods from all over the world but it has reached its limit.

YJIA: Speaking of China, how do you see the global financial order changing as China moves in to the role of global lender of last resort, particularly for struggling EU countries?

Cavallo: I do not think China will become a lender of last resort for EU countries. Its currency is not yet convertible and the only way China could help Europe is by diversi- fying its financial assets away from dollar-denominated bonds into Euro-denominated bonds. But I think in that case, they will look for bonds from Germany or other northen European countries rather than the countries in crisis. The lending of last resort for Europe should come from Europe itself and the United States. Only the Federal Reserve and the ECB have the capacity of issuing widely accepted money in the global economy. China and other emerging economies could help to channel funds via the IMF, but this will always be a complementary source of financing, not the most important.

Mohan: China’s capital account is not yet fully open, nor is its currency fully convertible. So it will take some time before China becomes a full participant in global financial markets. I also do not expect it to act as a lender of last resort for European countries without adequate IMF participation. As its economic and financial weight increases, and as it approaches greater financial openness, however, the world will have to give China its rightful place in the governance of international institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. Thus, I do see the global financial order changing, but conditional on China’s own actions to do with its financial sector, and the rest of the world’s recognition of its growing economic and financial weight.

YJIA: Some have argued that the Washington Consensus economic medicine of the 1990s—the “standard” liberal orthodoxy which prescribed open markets with a limited role for government in the economy—achieved macroeconomic stability in developing countries but contributed to greater economic inequality. As the advanced economies now focus on reduced public spending and exercising fiscal restraint in the current global crisis, how do you evaluate those policies based on your experiences with economic crisis in Argentina and India, respectively?

Cavallo: I do not think that greater economic inequality is the consequence of policies that achieved macroeconomic stability. On the contrary, if the same economic growth had been achieved with inflationary policies—like those that prevail when macroeconomic balance is neglected, using the argument that government interventions could replace fiscal and monetary discipline—inequality would be even greater. Of course, inequality could be kept within traditional patterns if growth were not a target. When an economy grows fast thanks to investment and implementation of more advanced technologies, inequalities increase in favor of those that risk their capital and provide the human skills required by those technologies. This is an inevitable outcome, whatever the degree of government intervention in the economy. Inequality probably increased more in China during the last 30 years than in the emerging countries that have applied Washington Consensus policies.

Mohan: First, let me clarify that India has not suffered the kind of economic crisis that Argentina suffered, and what countries like Greece and other European countries are suffering. We did have a balance of payment crisis in 1991 but did not default, and positive economic growth was restored within a year. However, I have addressed this general issue in my recent book, Growth with Financial Stability: Central Banking in an Emerging Market. One of the most interesting features of the current international economic and financial crisis is that in no Asian or Latin American economy has any financial institution exhibited the kind of stress that North American and European institutions have suffered. After the Latin American crises of the 1980s and 1990s, and the Asian crisis of the late 1990s, all these emerging market economies (EMEs) took to heart the nostrums that they had been prescribed by the Washington Consensus: adoption of free markets, flexible exchange rates, development and liberalization of financial markets and, above all, prudent macroeconomic and fiscal policies. In addition, in light of their experience with financial crises, they practiced more stringent and intrusive financial regulation, along with some degree of intervention in forex [foreign exchange] markets and capital account management, while practicing flexible exchange rates. In brief, they have recognized the importance of flexible and open markets, but have tempered this free market philosophy with a better understanding of the role of government and regulation that is necessary for the efficient functioning of markets.