Global AI Governance and the United Nations

The UN Should Update Its Existing Institutional Framework Instead of Creating a Global AI Agency

August 6, 2013. Foreign Minister Ricardo Patiño participated in the United Nations Security Council. Source: Xavier Granja Cedeño

By Ryan Nabil

I. Introduction

As national governments and world leaders grapple with the complexities of AI governance, the United Nations faces growing calls to establish a global agency dedicated to artificial intelligence.[1] However, given the distinct policy challenges that AI poses in different domains of global governance, a single, global AI agency is unlikely to address such a wide variety of issues effectively. Furthermore, such an overly broad organization will encounter difficulties in managing the competing strategic priorities and divergent political values of the UN’s heterogeneous and increasingly divided member base. Instead of creating an international AI organization without a specific mandate, the United Nations should consider launching agency-specific AI initiatives within its existing institutional framework.

As future AI risks — from biometric surveillance to autonomous weapons systems — become better understood, international leaders have sought to propose new ideas for AI regulation. One such suggestion that has enjoyed growing popularity is the idea of creating an international organization for AI. Most recently, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres and Technology Envoy Amandeep Gill have voiced their support for creating a global agency to address future AI safety risks and foster global cooperation.[2] Such support comes against the backdrop of similar calls by United Kingdom Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman.[3] Many such leaders draw parallels between AI safety risks and global challenges like atomic energy and nuclear proliferation, arguing that a global AI agency is needed to mitigate emerging threats.[4]

In response to calls for global AI governance, while some policy experts have understandably dismissed such proposals, it is becoming increasingly evident that global AI governance is an increasingly complex and crucial issue that merits closer examination and a more meticulous, deliberative approach.[5]

As a starting point, UN leaders and international policymakers must grapple with a series of questions to gain a deeper understanding of AI governance and explore various institutional models for AI governance at the multilateral level. First, when world leaders advocate the creation of a global AI agency, how do they envision such an organization? Second, given the significant differences between various international organizations regarding their functions and institutional designs, what taxonomy could help categorize and analyze possible institutional models for AI governance? Third, since AI is frequently compared to nuclear technology, how do AI and nuclear regulation differ, and what do these differences mean for AI governance?[6] Finally, what are the challenges of creating a global AI agency, and what role should the UN seek to play in the emerging institutional architecture for AI governance?

While these questions are pivotal to defining the UN’s future role in AI governance, addressing each question in detail would exceed the scope of this brief essay. Instead, recognizing the limited academic and policy scholarship on AI and global governance, this essay seeks to provide insights into potential institutional frameworks for international AI regulation. By doing so, it seeks to contribute to the emerging body of scholarship on how the United Nations can engage more effectively with the emerging institutional framework for global AI governance.

II. Global AI Governance and Taxonomy of International Organizations

While a growing number of international leaders advocate the creation of a global AI agency, there appears to be considerable variation in the types of organizations they endorse. For instance, Prime Minister Sunak has proposed the creation of an international entity akin to the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN), which serves as an intergovernmental center for research and cooperation in particle physics.[7] Meanwhile, some business figures like Sam Altman support the founding of an institution like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), but tailored for AI regulation.[8] However, a CERN-like research center would likely differ fundamentally from an entity modeled after the IAEA in its institutional design and functions. Given such differences, the United Nations would benefit from conducting a more systematic analysis and evaluation of possible institutional models for AI governance.

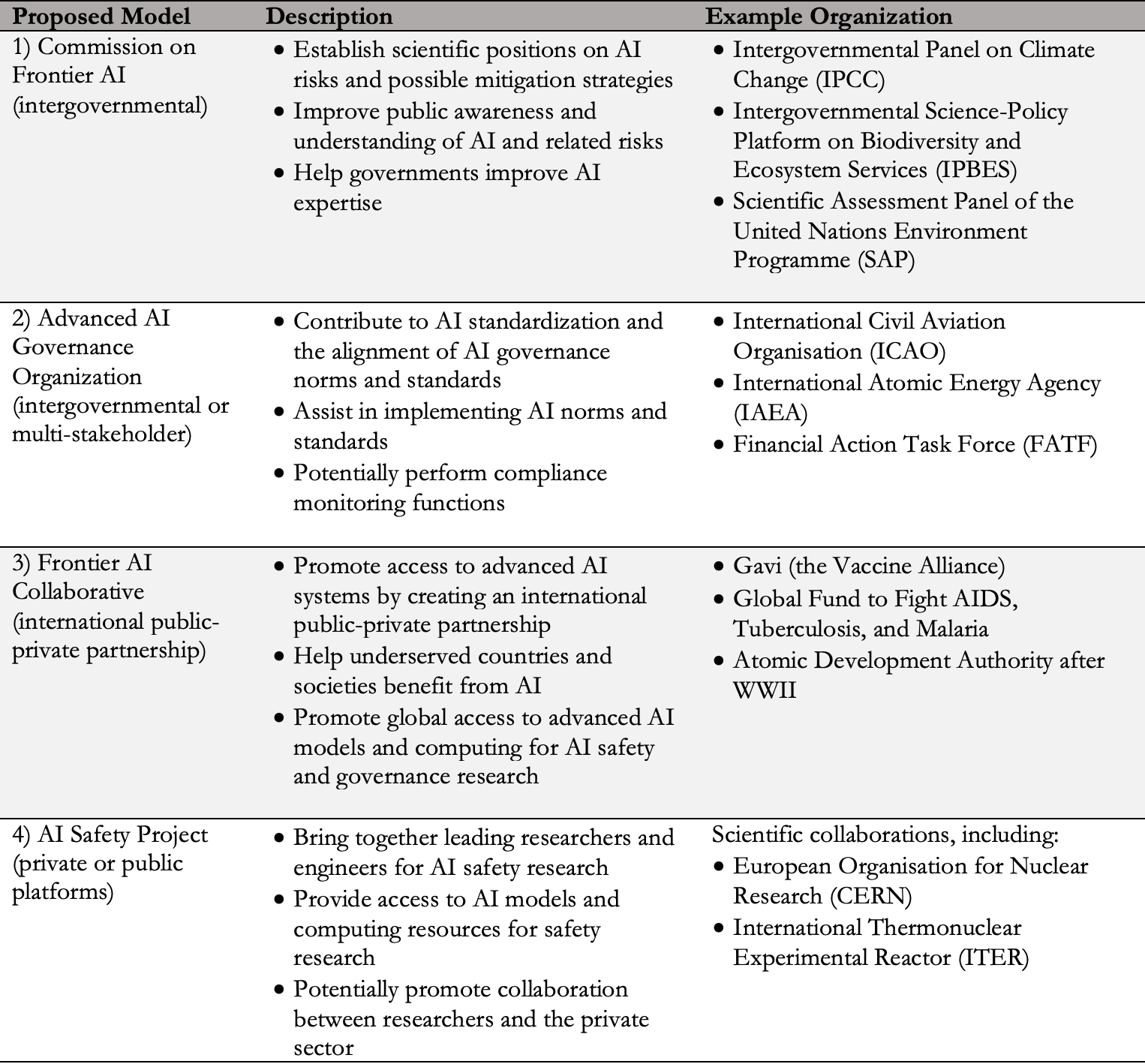

A recent paper authored by leading technology and international relations researchers from Google DeepMind, Oxford University, Stanford University, and Université de Montreal serves as a valuable starting point for such discussion.[9] More specifically, the authors put forward four possible models for an international AI organization: i) Commission on Frontier AI, ii) Advanced AI Governance Organization, iii) Frontier AI Collaborative, and iv) AI Safety Project (Table 1). The primary challenge with this taxonomy is its limited consideration of distinct aspects of AI governance, such as arms control, human rights, and trade policy, each necessitating distinct institutional arrangements to address related policy effectively. However, within the context of a specific domain, such as laws of war, the proposed framework can contribute to the ongoing debate on the most suitable institutional models for AI governance.

Evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of possible models can also help clarify whether the United Nations would be the most suitable platform for certain institutional functions. For example, a CERN-like research center (“AI Safety Project”) would ideally provide advanced computing resources and cloud platforms to facilitate research collaboration between leading technology companies, universities, and governments (Table 1). However, given that AI capabilities tend to be concentrated in a handful of countries and technology companies, such initiatives might be more effective as an intergovernmental project by like-minded and technologically advanced countries — or even as consortia of technology companies and research institutions with funding from host governments. Therefore, instead of creating a CERN-like organization, the UN’s efforts might be more effective in other areas, such as AI-related technical standards and AI ethics, where the UN could benefit from a stronger comparative advantage and draw more effectively from its extensive institutional expertise.

Table 1. Taxonomy of Possible Institutional Models for Global AI Governance

Source: Ho et al. (2023) [10]

III. The Lack of International Consensus on AI Governance and What It Means for the UN

The United Nations should exercise caution against creating an overly broad global AI agency without a specific mandate, especially given the institutional challenges inherent in designing and operating such an institution. Among the four suggested models, variations of the second model — a global AI agency or “advanced AI governance organization” — appear to be the most commonly suggested institutional framework by international leaders, including António Guterres and Amandeep Gill (Table 1). Advocates of this model tend to argue that advanced AI systems will create existential and other risks as they develop further. Similar concerns were also expressed during the development and spread of nuclear technologies. Building upon this analogy, proponents emphasize the necessity of a global AI agency to address AI safety risks, drawing a parallel with the role of international organizations in monitoring and regulating international uses of atomic energy and preventing nuclear proliferation.[11]

Given certain similarities between AI and nuclear technology, it is all too understandable why world leaders might be inclined to draw a comparison between the two. As is the case with electronics, automobiles, and modern medicine, both AI and nuclear technology are general-purpose technologies that can promote growth and innovation across various sectors of the economy. Additionally, nuclear and AI systems are also dual-purpose technologies. While they can promote innovation and growth, atomic energy and artificial intelligence can also be used in developing offensive capabilities, with nuclear weapons and AI-enabled autonomous weapons being two obvious examples, respectively.

Notwithstanding these general similarities, their differences mean that AI governance will require a different institutional approach. A fundamental distinction derives from the predominantly physical and digital nature of the two technologies and the highly classified nature of nuclear expertise.[12] Unlike AI, nuclear energy is inherently physical, reliant on highly sophisticated nuclear reactors and fissile materials for the generation of atomic energy.[13] Using nuclear energy also requires often highly classified knowledge of nuclear science and engineering, as well as occupational privileges or high-level clearance from governments of nuclear states. In contrast, while advanced AI systems do require advanced physical computing infrastructure, the constraining input factors are often digital and easier to access: the availability of high-quality data sets, training models, and algorithms, along with much less regulated and restricted access to AI knowledge and expertise. The broader availability of these input factors results in significantly lower barriers to entry in AI compared to nuclear technologies.[14]

That is one reason why, whereas only a handful of state actors dominate the nuclear sector, the private sector plays a much more important role in artificial intelligence. For example, in the United States, while the defense establishment has played a critical role in developing certain advanced AI capabilities, recent AI innovation has been largely driven by a diverse range of actors, including technology firms, startups, research organizations, and even academic institutions. Due to the importance and heterogeneity of such non-state actors, AI regulation is fundamentally more multifaceted than nuclear governance and requires a more differentiated, nuanced approach.[15] Consequently, an IAEA-like organization designed to monitor the compliance of foreign governments and nuclear plants with the relevant regulations would be much less appropriate for AI governance.

Finally, and most importantly in the context of international organizations, nuclear risks can be defined more concretely than AI safety risks. Although the Chinese, Russian, and U.S. governments might differ in their conceptions of international law and global governance, they would nevertheless tend to agree that nuclear proliferation is generally harmful to international security. In contrast, long-term, existential AI risks remain a subject of intense scholarly and policy debates. The resulting lack of scientific consensus means that any international organization will face significant challenges in identifying, agreeing upon, and prioritizing long-term AI risks, as well as developing mechanisms to address them.[16] This potential for disagreement poses a major challenge to future AI governance initiatives, albeit potentially less so if such efforts target more specific, well-defined areas of AI governance.

However, even in narrowly defined contexts, multilateral initiatives might struggle to find a meaningful consensus among member states, as evidenced by the recent difficulties in the UN’s efforts to regulate lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS).[17] Whereas some governments, like Brazil, advocate a ban on autonomous weapons, many others support regulating LAWS, while several countries oppose such multilateral efforts altogether.[18] Most recently, in October 2023, the General Assembly passed its first resolution on autonomous weapons, stressing the growing need to understand and address the challenges posed by the use of LAWS.[19] However, five countries, including India and Russia, voted against the resolution, while China, Israel, Turkey, and five other countries abstained.[20] Such disagreements, even in the context of a relatively straightforward non-binding resolution on autonomous weapons, highlight the challenges the UN faces in achieving consensus even on specific, narrowly defined issues. The challenges of reaching meaningful consensus on more general, vaguely defined AI risks — as would be the case under a global AI agency without a narrowly defined mandate — would likely be much greater.

While meaningful international consensus on long-term AI risks remains elusive, short and medium-term AI risks vary widely according to the precise sectors and contexts in which AI-enabled tools are applied. Mitigating such risks will ultimately require differentiated institutional approaches than what would be possible under a one-size-fits-all global AI agency. For example, one can consider three areas in which AI applications pose important but distinct risks. First, as discussed above, a major risk that AI poses in the context of international security is the development and more widespread use of lethal autonomous weapons.[21] Second, facial recognition and surveillance technologies pose significant challenges to civil liberties, especially in countries with poor human rights records.[22] Third, since AI capabilities tend to be concentrated in a handful of countries, the question of how developing and emerging-market countries can develop AI capabilities and leverage artificial intelligence to promote economic growth is becoming an increasingly crucial one for international development.[23]

These examples represent three distinct risks in the fields of arms control, human rights, and international development, respectively, where AI regulation will require different policy approaches and domain-specific institutional frameworks. The variety of contexts in which AI poses unique challenges underscores the difficulty of creating a one-size-fits-all global agency for AI, especially when compared to institutional frameworks for monitoring and regulating nuclear energy. Instead, the UN’s efforts might be better spent by identifying domain-specific AI policy challenges where it has a comparative advantage and developing AI-related initiatives within the context of existing UN institutions.

To that end, the United Nations could establish working groups consisting of experts and other stakeholders to help identify and evaluate AI-related policy areas where the UN can play an active role. Once such areas are identified, the UN should identify and evaluate potential AI-related risks and set its policy objectives within the context of those domains. The four institutional models described earlier could also help the UN evaluate which frameworks best suit the UN’s policy objectives in these domains. Based on such analysis, UN leaders and international policymakers can make more informed decisions about the extent to which the United Nations should collaborate with other multilateral institutions — such as the World Bank and the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — and whether certain complex issues might eventually necessitate the creation of specialized UN bodies.

IV. Examples of Areas Where the United Nations Could Play an Effective Role in Global AI Governance

While creating a new global AI agency without a specific mandate would not be the best way forward, the United Nations can still define a meaningful role within the emerging institutional architecture for global AI governance. That is why international policymakers must think more creatively about the areas where the UN enjoys a comparative advantage vis-à-vis other international actors and how it can play a constructive role, even in the face of significant political challenges and institutional constraints.

While the United Nations continues to face significant challenges stemming from the diverse and sometimes conflicting strategic interests of its member states, the UN still maintains a distinct position in international governance as a truly international institution. While several multilateral and regional actors — such as the European Union, the OECD, and the Global Partnership on AI — have recently become active in AI governance, their membership base is often restricted. In contrast, despite its institutional shortcomings, the United Nations still brings together virtually all developed and developing countries, many of which are typically underrepresented in most AI governance debates. With the right institutional approach, the UN can play a unique role in AI governance by providing a more inclusive and globally representative platform for international AI dialogue, setting it apart from other regional and multilateral actors.

Nevertheless, normative disagreements among rival powers (e.g., China, Russia, and the United States) and even like-minded countries (e.g., the United States and EU member countries) regarding different aspects of AI governance would still pose a major challenge.[24] Given this challenge, the UN is more likely to be successful in its AI governance efforts by focusing on the development of voluntary AI frameworks and agreements, similar to the OECD’s creation of AI principles and regulatory frameworks for developed economies.[25] Such voluntary AI governance initiatives could be especially helpful for developing and emerging-market economies that might lack the resources and regulatory expertise to formulate their own AI frameworks and thus look to multilateral institutions and foreign governments for guidance on such issues.

However, the success of such endeavors hinges significantly on the UN leadership’s awareness of institutional constraints and their strategy to overcome such challenges. First, it is crucial to recognize that much of the world’s cutting-edge AI expertise and technological capabilities tend to be concentrated within a handful of countries and companies within those countries. To play a more effective role in AI governance, the UN and its agencies must invest in their AI policy expertise while formulating a strategy to engage with a wide range of stakeholders, including the private sector, academic and policy organizations, and civil society. In this context, the recent establishment of the High-Level Advisory Board on Artificial Intelligence represents a positive step in this direction. Exploring additional avenues to collaborate with diverse stakeholders will allow the UN to learn from their expertise and play a more effective role in global AI governance.

Second, given the current geopolitical circumstances, efforts related to non-military applications of AI are likely to be more effective than focusing primarily on defense and security aspects of AI. That is particularly the case because many security-related AI governance issues, such as the rules for the development and deployment of LAWS, are characterized by strong disagreements between the Permanent Members of the UN Security Council and other major states with significant defense capabilities, such as India, Israel, and Turkey. By focusing on less polarized aspects of AI governance, the UN could build much-needed institutional capacity and global reputation, improving its potential to contribute to more challenging aspects of AI governance in the future.

Finally, as discussed, the diverse and often conflicting strategic interests of various UN members, both between and within developed and developing countries, will pose considerable challenges to any future AI governance initiatives. Acknowledging and working within these constraints can allow the UN to play a more effective role in AI governance. For example, instead of seeking to impose new AI principles and rules globally, the UN could identify areas where it could serve as an information hub and resource for developing and least-developed countries. By doing so, UN agencies could help national governments address AI-related challenges that are particularly important within the specific economic and political context of individual member countries.

In this context, the United Nations could play a meaningful role in enabling developing countries to establish national mechanisms to identify and mitigate AI safety risks. To that end, the UN could help create multi-stakeholder working groups that evaluate AI risks in different domains and recommend possible mitigation strategies. The UK government has proposed a similar risk assessment framework as part of its recent AI White Paper, and a similar framework could also be helpful for developing countries in evaluating different AI risks.[26] Such evidence-based, impartial analysis from the UN could serve as an additional resource for member states as they develop and calibrate their national AI policies. Furthermore, the UN could draw upon its extensive institutional expertise in technical standards and enable the International Telecommunications Union and related working groups to play a more active role in the development of AI-related technical standards.

V. Conclusion

To paraphrase the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s seminal Foreign Affairs essay, the international order currently appears to be in the middle of a Zeitenwende — a period of significant historical shift — as emerging technologies and rising powers create new challenges for global governance.[27] Against this backdrop, the United Nations can play a constructive role by providing a platform for intergovernmental dialogue, enabling member states to design better regulatory frameworks, and promoting international cooperation in developing AI norms and standards. To that end, the United Nations needs a measured, pragmatic approach that reflects its comparative advantages and institutional strengths and considers current institutional constraints and emerging geopolitical challenges.

In the long term, it could well be the case that addressing certain AI-related policy challenges might require the creation of new institution(s) within or outside the UN architecture. However, at a time when the precise long-term risks are unclear and subject to significant debate, the UN should instead focus on clearer, pressing challenges where it can play a constructive role. To do so, the United Nations should first identify domain-specific AI policy challenges and consider whether the UN’s institutional design and comparative advantages are well-suited for policy efforts in those domains. Likewise, UN agencies with an AI nexus should be encouraged to develop the required expertise to help address AI-related policy challenges within their purview. Instead of prematurely creating a global AI agency without a specific mandate, a more flexible, well-calibrated, and iterative approach would allow the UN to play a more effective role in the emerging institutional architecture for global AI governance.

About the author

Ryan Nabil is the Director of Technology Policy and Senior Fellow at the National Taxpayers Union Foundation (NTUF), a think-tank in Washington, DC. Mr. Nabil formerly worked as a Research Fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute and a Fox Fellow at the Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris (Sciences Po). He is also an MA graduate of the Yale Jackson Institute, where he served as the managing editor of the Yale Journal of International Affairs and research fellow (delegate) at the Stanford U.S.-Russia Forum. This essay is based on the author’s letter to His Excellency Amandeep Singh Gill, the UN Secretary-General's Envoy on Technology, in preparation for the inaugural meeting of the newly founded United Nations High-Level Advisory Board on Artificial Intelligence.

Endnotes

Will Henshall, “How the UN Plans to Shape the Future of AI,” Time, September 21, 2023, https://time.com/6316503/un-ai-governance-plan-gill/.

Henshall, “UN Plans to Shape AI”; Brian Fung, “UN Secretary General Embraces Calls for a New UN Agency on AI in the face of ‘potentially catastrophic and existential risks,’” CNN, July 18, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/07/18/tech/un-ai-agency/index.html.

Daniel Martin, “The Five Key Points on Rishi Sunak’s Agenda for His Meeting with Joe Biden,” The Telegraph, June 8, 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2023/06/06/rishi-sunak-joe-biden-washington-ai-london-watchdog/; Sam Altman, Greg Brockman, and Ilya Sutskever, “Governance of Superintelligence,” OpenAI, May 22, 2023, https://openai.com/blog/governance-of-superintelligence#GregBrockman.

Ian J. Stewart, “Why the IAEA Model May Not Be Best for Regulating Artificial Intelligence,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, June 9, 2023, https://thebulletin.org/2023/06/why-the-iaea-model-may-not-be-best-for-regulating-artificial-intelligence/.

For example, see Adam Thierer, Existential Risks & Global Governance Issues Around AI & Robotics (Washington, DC: R Street, 2023), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4174399.

Altman, Brockman, and Sutskever, “Superintelligence.”

Martin, “Rishi Sunak’s Agenda.”

Altman, Brockman, and Sutskever, “Superintelligence.”

Lewis Ho et al., “International Institutions for Advanced AI,” Computers and Society, July 10, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.04699.

Ho et al., “International Institutions for Advanced AI.”

Stewart, “IAEA Model for AI.”

The author thanks Ms. Lindsey Carpenter, Attorney at the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, for her insights on the topic.

Stewart, “IAEA Model for AI.”

Yasmin Afina and Patricia Lewis, “The Nuclear Governance Model Won’t Work for AI,” Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House), June 28, 2023, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/06/nuclear-governance-model-wont-work-ai; Stewart, “IAEA Model for AI.”

Ryan Nabil, “Comments to the White House: The Need for A Flexible and Innovative AI Framework,” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, July 7, 2023, https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/letter-to-the-white-house-the-need-for-a-flexible-and-innovative-ai-framework; Rishi Iyengar, “Who’s Winning the AI Race? It’s Not That Simple,” Foreign Policy, March 27, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/27/us-china-ai-competition-cooperation/.

Ekaterina Postnikova, “Совбезе ООН призвали не допустить создание «машин-убийц» на основе ИИ” [“The UN Security Council urged to prevent the creation of ‘killer machines’ based on AI”], RBC, July 18, 2023, https://www.rbc.ru/politics/18/07/2023/64b6c01f9a79477796c5b78c.

Shane Reeves, Ronald T. P. Alcala, and Amy McCarthy, “Challenges in Regulating Lethal Autonomous Weapons Under International Law,” Southwestern Journal of International Law 28, 2020, pp. 101–118, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3775864.

Sydney J. Freedberg, Jr., “‘Not the right time’: US to push guidelines, not bans, at UN meeting on autonomous weapons,” Breaking Defense, March 3, 2023, https://breakingdefense.com/2023/03/not-the-right-time-us-to-push-guidelines-not-bans-at-un-meeting-on-autonomous-weapons/.

The United Nations, Resolution on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems, A/C1/78/L56, October 12, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/gadis3731.doc.htm.

Ben Wodecki, “UN Approves Its First Resolution on Autonomous Weapons,” AI Business, November 10, 2023, https://aibusiness.com/responsible-ai/in-a-first-un-votes-on-autonomous-weapons-regulation.

John Lewis, “The Case for Regulating Fully Autonomous Weapons,” Yale Law Journal 124, no. 4, January–February 2015, p. 9, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/comment/the-case-for-regulating-fully-autonomous-weapons.

For instance, see Lewis, “Regulating Fully Autonomous Weapons.”

David Zhang et al., “Chapter 4: The Economy and Education” in “The AI Index 2022 Annual Report,” AI Index Steering Committee, Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, March 2022, pp. 172–195, https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2022-AI-Index-Report_Master.pdf.

For example, see Postnikova, “The UN Security Council.”

La Cour des comptes [The French Court of Auditors], “Comparaison de 10 stratégies nationales sur l’intelligence artificielle” [“Comparison of Ten National AI Strategies”], April 2023, https://www.ccomptes.fr/system/files/2023-04/20230403-comparaison-strategies-nationales-strategie-nationale-recherche-intelligence-artificielle.pdf.

UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, “A Pro-Innovation Approach to AI Regulation,” CP 815, March 29, 2023, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-regulation-a-pro-innovation-approach/white-paper; Nabil, “Comments to the White House.”

Olaf Scholz, “Die globale Zeitenwende: Wie ein neuer Kalter Krieg in einer multipolaren Ära vermieden werden kann” [“The Global Zeitenwende: How to Avoid a New Cold War in a Multipolar Era”], Foreign Affairs, December 5, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/germany/die-globale-zeitenwende.