Kosovo: Realities of Peacekeeping

By Esther Owens

Plagued by a history of violent ethnic tension between Kosovar Serbs and Albanians, Kosovo unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in February 2008. Although Serbia refuses to recognize the former territory’s sovereignty, Kosovo has gained diplomatic recognition by a majority of U.N. member states. These photographs capture a people and a territory that have been under international occupation since 1999. Before the 2008 declaration of independence, the U.N. mission handled all administrative tasks of a state; from issuing marriage certificates to management of waste collection. As a result, Kosovar Serbs living in ethnic enclaves continue to rely on Belgrade for public services such as healthcare and education.

Thousands of Kosovar Serbs struggle daily with reconciling the competing demands of Pristina in Kosovo and Belgrade in Serbia. Official documents such as automobile registration, education credentials, and travel identification issued by Pristina are not recognized by Belgrade; and having Pristina-issued documents can prevent Kosovar Serbs from availing themselves of public services in Belgrade.

Given the large-scale economic and human devastation of the war, court systems are important for post-conflict reconciliation and trust-building. Yet, the Kosovo court system uses Albanian as the only official language. Therefore, Serbian-speaking Kosovars are effectively disenfranchised from the court systems. Widespread inability to reconcile property rights and missing-persons cases is one of the most serious impediments for meaningful reconciliation and economic growth.

Kosovo adopted the Euro in 2002, yet is not a member of the Eurozone. Thus, Kosovar policymakers cannot exercise monetary policy. Serbian enclaves still illegally accept Serbian Dinars, and many Kosovar Serb-owned establishments list prices in Dinars but accept Euros as payment. Lack of a coherent monetary policy, a failure to invest in infrastructure, and weak economic growth have exacerbated unemployment.

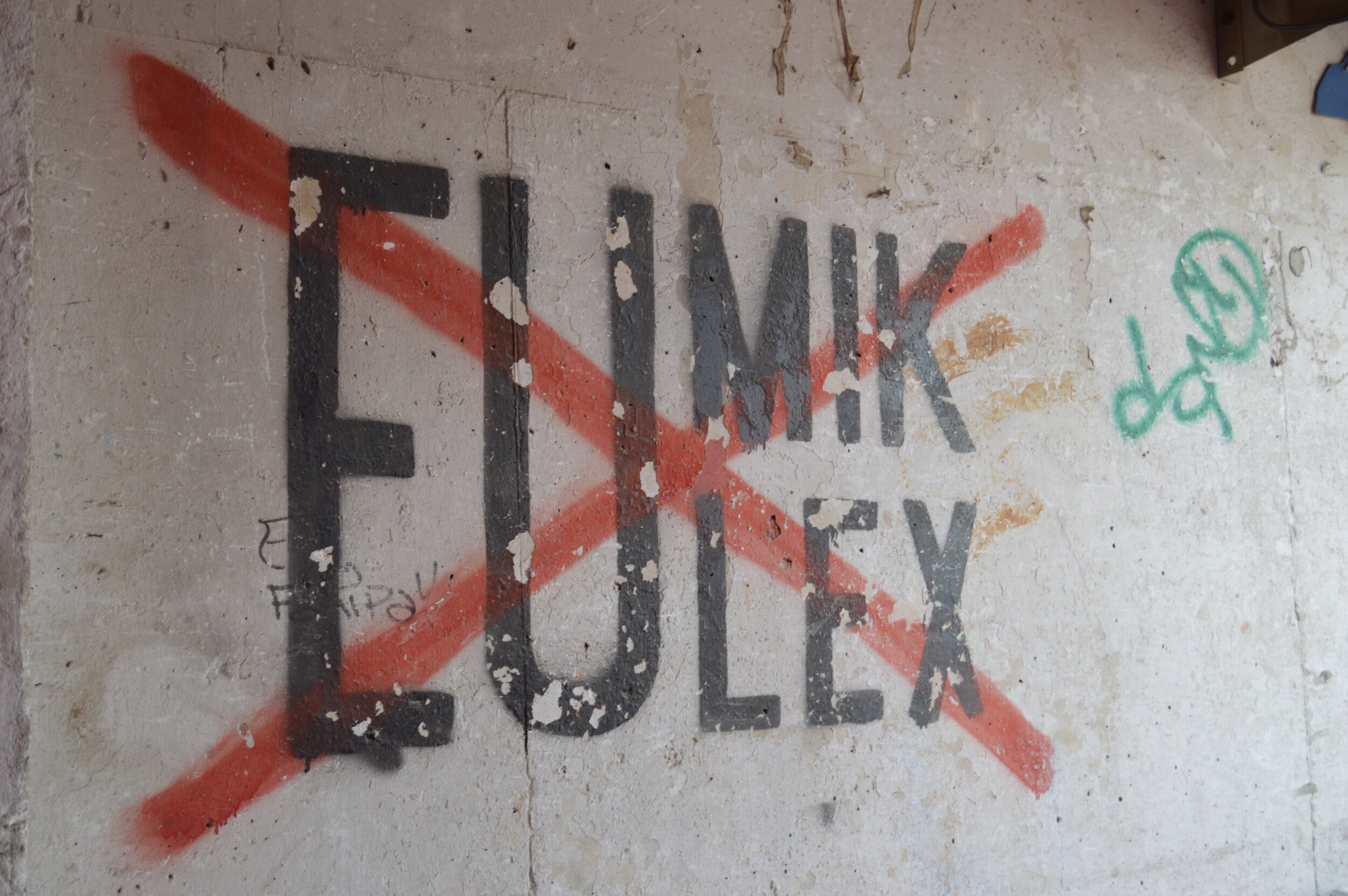

Many Kosovars are ambivalent about the presence and effect of international actors. They are simultaneously critical of the perceived impediment to autonomous statehood; yet, they are heavily reliant on the influx of foreign investment and aid.

Until very recently, Belgrade, backed by Russia, has called for the withdrawal of international organizations. Since the election of Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić, Belgrade has grown increasingly more amenable to Kosovo exerting its authority. At the same time, Pristina has become increasingly impatient with a decades-long occupation and no sign of autonomous statehood. This tension routinely plays out in the quarterly U.N. Security Council Meetings, where there is a clear division among the five permanent members.

In this sense, Kosovo continues to serve as a proxy for the battle between the two sides of Cold War that is anything but resolved. These photos capture the ambivalence, the struggle for several generations of Kosovars in an increasingly fraught geopolitical landscape.

About the Author

Esther Owens studies Environment and Energy and International Security Policy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. She is the managing editor of the Columbia University’s Journal of International Affairs and the head comedy writer for SIPA’s annual Apollo comedy show, Follies.