My Space? The Transformation of Ethiopia’s Capital Addis Ababa

By Manuela Graetz, Geo Kalev, and Marjan Kloosterboer

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia is a young city. Founded in 1886 by King Menelik II and Queen Taitu, in its first decades the city grew organically, without any formal planning.[1] Addis Ababa’s establishment represented a change for the nation as a whole—it was envisioned as a “modernist monument” that would function as a catalyst for Ethiopia to enter the world economy.[2] Today, Addis Ababa is undergoing a massive transformation. With approximately 4 million inhabitants, the city population is still small, but with a fast growth rate of 3.5 percent per year.[3]

Most of the city’s physical structure is swiftly changing. For instance, the construction of the first light rail train in Sub-Saharan Africa was recently completed. The rationale behind this development is to brand the city as Africa’s diplomatic capital

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia is a young city. Founded in 1886 by King Menelik II and Queen Taitu, in its first decades the city grew organically, without any formal planning. [1] Addis Ababa’s establishment represented a change for the nation as a whole—it was envisioned as a “modernist monument” that would function as a catalyst for Ethiopia to enter the world economy. [2] Today, Addis Ababa is undergoing a massive transformation. With approximately 4 million inhabitants, the city population is still small, but with a fast growth rate of 3.5 percent per year. [3]

Most of the city’s physical structure is swiftly changing. For instance, the construction of the first light rail train in Sub-Saharan Africa was recently completed. The rationale behind this development is to brand the city as Africa’s diplomatic capital and international hub, thereby helping Ethiopia become a middle-income country.[4]

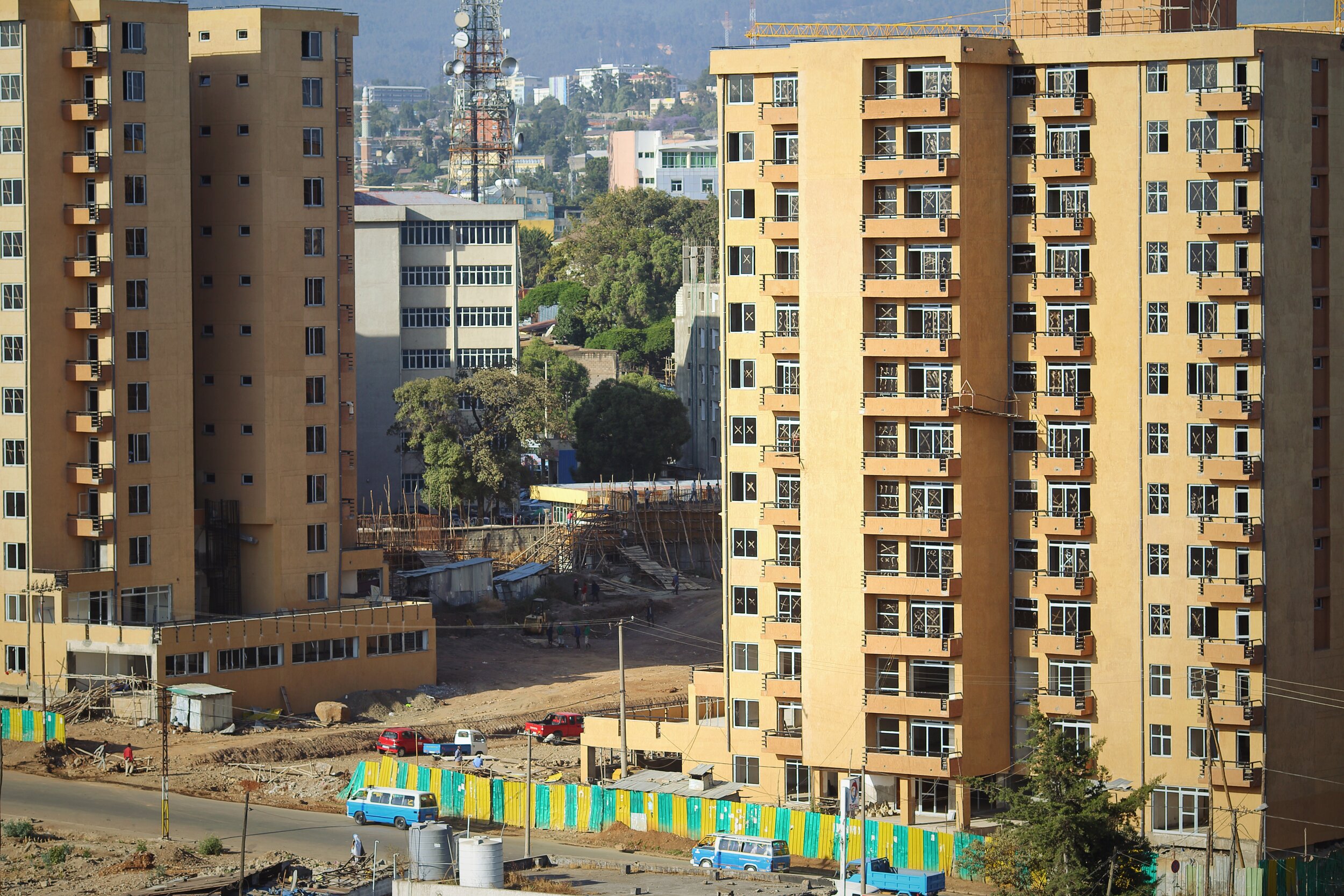

Built through tabula rasa clearing in the four inner-city sub-sections, the new Central Business District showcases Addis Ababa as a modern, globally competitive city that adheres to international standards, creating a business friendly environment. Through aesthetic inter-referencing of the built environment with other global cities such as Shanghai and Dubai, its skyline and signature buildings project Addis Ababa’s political and economic ambitions. The downside is that it creates a homogenous environment and a shared visibility with other cities, causing the city to lose its “sense of place” and strong cultural identity.

Addis Ababa is one of the safest cities in Africa. However, this is rapidly changing due to the segregation of population groups. The new Central Business District might grow in a form of splintered urbanism, where low-income groups are pushed out of the center and the servicing of the central areas is prioritized over meeting basic needs elsewhere.[5] This social and spatial segregation of population groups can potentially be a form of polarization that will put the city’s existing social fabric and social cohesion at risk, compromising future safety.

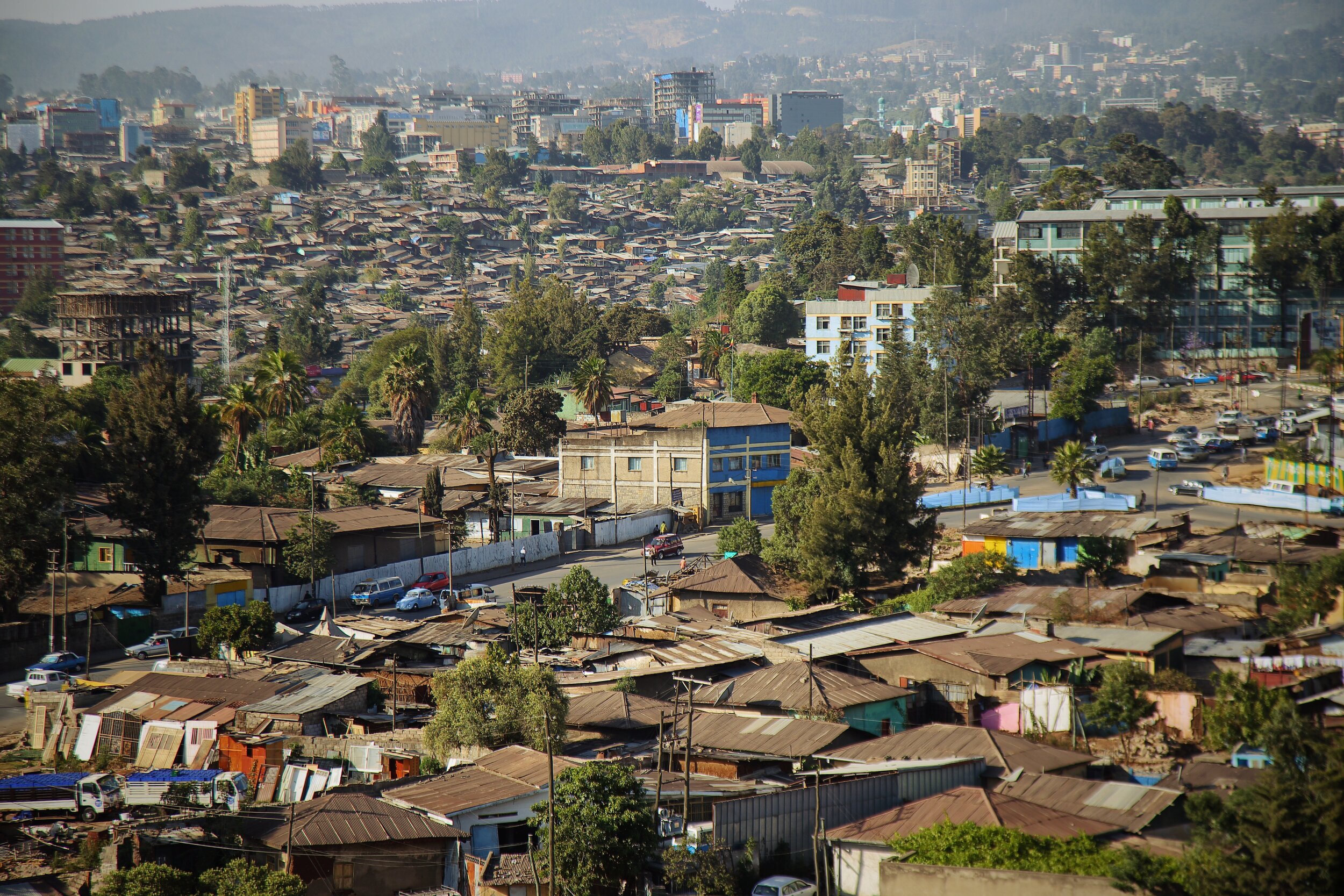

Currently, slums comprise 80 percent of the city. The predominantly low-rise and low-density housing is made of traditional building materials. In addition to the poor condition of the current housing stock, the city is also facing a tremendous housing backlog.[6] In contrast with the city’s horizontal expansion since its establishment, the city’s boundaries have now been reached, creating the need to expand vertically. In 2005 the Integrated Housing Development Programme was launched. Its main aim is to address the housing backlog, improve access to urban services, and offer relocation homes for urban dwellers displaced from the inner-city renewal areas, while creating job opportunities.[7]

However, UN-Habitat research shows that low-income households still cannot afford housing units that are compatible with their family size. Therefore, there are no sustainable solutions to the city’s current housing problems. [8] Although households that relocated from the inner-city areas to make space for development are supposed to be compensated, this is often not the case. For instance, informal households are ineligible for compensation. Urban dwellers continue to rent in the private sector in another area or informally build shelters wherever they can until urban development forces them to move further.

About the Author

Manuela Graetz is an urban and regional planner and has spent more than eight years working on urban development in Ethiopia, especially in the area of housing. Her wish is for the cultural, spatial, and natural treasures of Addis Ababa to receive recognition and survive the aggressive desire for “international style” transformation. manuela.graetz@gmail.com

Geo Kalev is a photographer from Sofia, Bulgaria. He is the founder of Studio Fo. He came to Addis Ababa to support the first African Circus Festival in December 2015. www.geokalev.com www.studiofo.net

Marjan Kloosterboer is an urban researcher based in Addis Ababa. Kloosterboer teaches at the Ethiopian Institute of Architecture Building Construction and City Development EiABC. She is currently a PhD student at Glasgow University, researching the transformation process of Addis Ababa. marjankloosterboer@gmail.com

Endnotes

Dandena Tufa, “Historical Development of Addis Ababa: plans and realities,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 41 (2008): 27-59.

Shimelis Bonsa Gulema, “City as Nation: Imagining and Practicing Addis Ababa as a Modern and National Space,” Northeast African Studies 13 (2013): 167–213.

Ministry of Urban Development, Housing and Construction of Ethiopia, National Report on Housing & Sustainable Development (2014). Maria Cristina Pasquali, Addis Ababa: End of an Era, (Addis Ababa: Shama Books Plc, 2014).

AASZDPPO, Addis Ababa and Surrounding Oromia Special Zone Integrated Development Plan, (2013).

Watson, Vanessa, “African urban fantasies: dreams or nightmares?,” Environment and Urbanization 26 (2014) : 561–567.

United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-HABITAT), Situation Analysis of Informal Settlements in Addis Ababa, Addis Ababa Slum Upgrading Programme, and Cities Without Slums Sub-Regional Programme for Eastern and Southern Africa, (2007).

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), The Ethiopia Case of Condominium Housing: The Integrated Housing Development Programme, 2011.

Ibid.