Growing Up Cambodian: Childhood and Crisis Three Decades after the Khmer Rouge

By Nathan William Meyer

It was Year Zero. Books were burned, religion outlawed, money abolished, schools closed, and teachers, doctors, and lawyers killed. Wearing glasses or speaking a foreign language was crime enough to merit death. Families were turned out of homes, cities emptied, and a nation was slowly worked to death in the paddy fields. Empty schools were made into prisons and suspected spies tortured in classrooms before being clubbed with shovels, stabbed with bamboo sticks, or kicked to death to save bullets. Infants’ heads were dashed against tree trunks so they could not live to avenge their parents. It was Year Zero; it was 1975.

The Khmer Rouge overthrew the Cambodian government in that year and by the time Vietnam forced the regime from power in 1979, Cambodia’s population had plummeted from seven to just 4.8 million people. Clawing out of this national grave, the Cambodian people found desolation in what the international community called peace- homes and lives destroyed, and families scattered or rotting in muddy killing fields. With the economy shattered and the educated and skilled classes reduced to bones in mass graves, those who survived the genocide inherited only the dirt under their feet. The Khmer Rouge was gone, but Cambodia had to start from scratch.

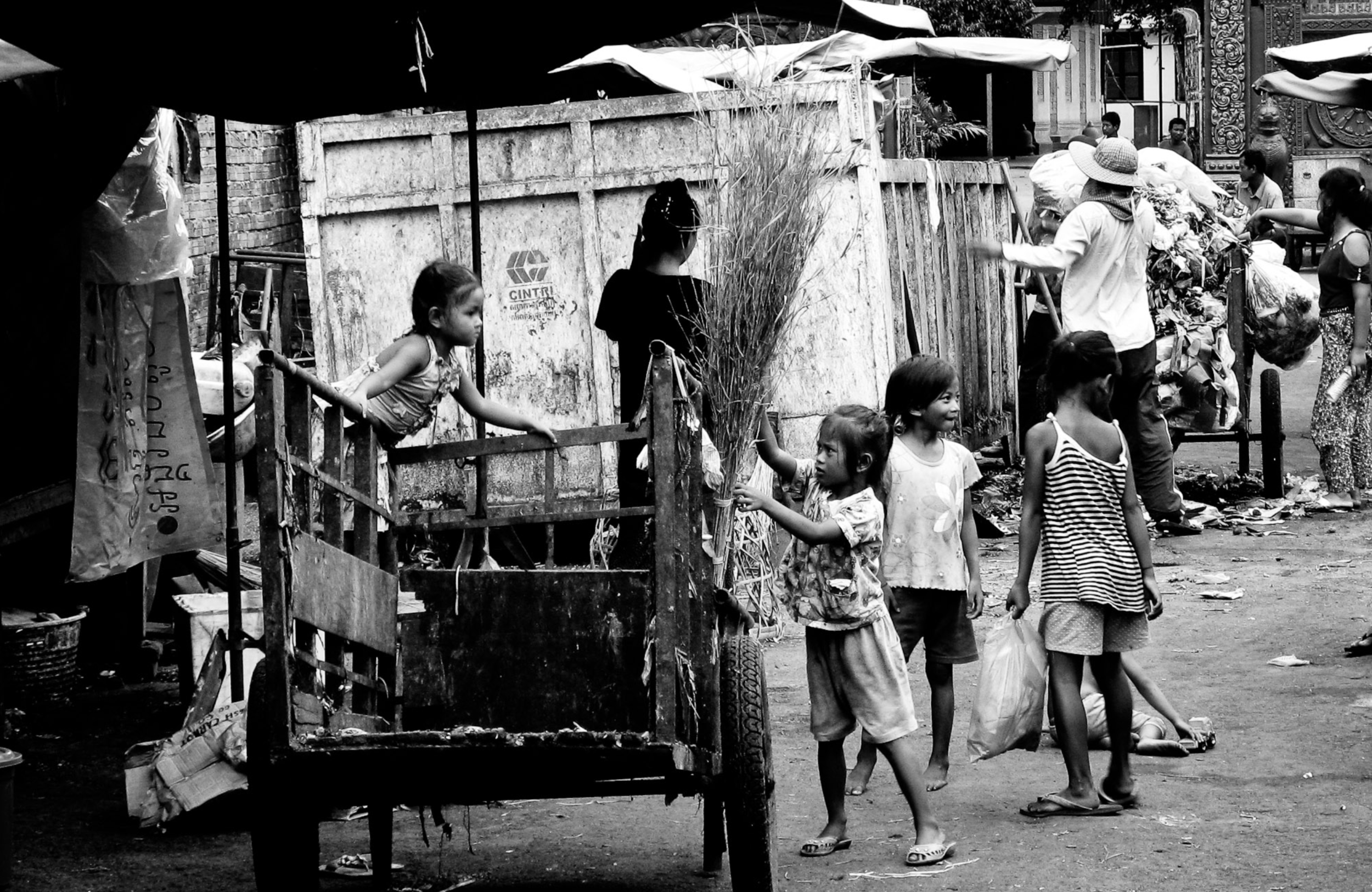

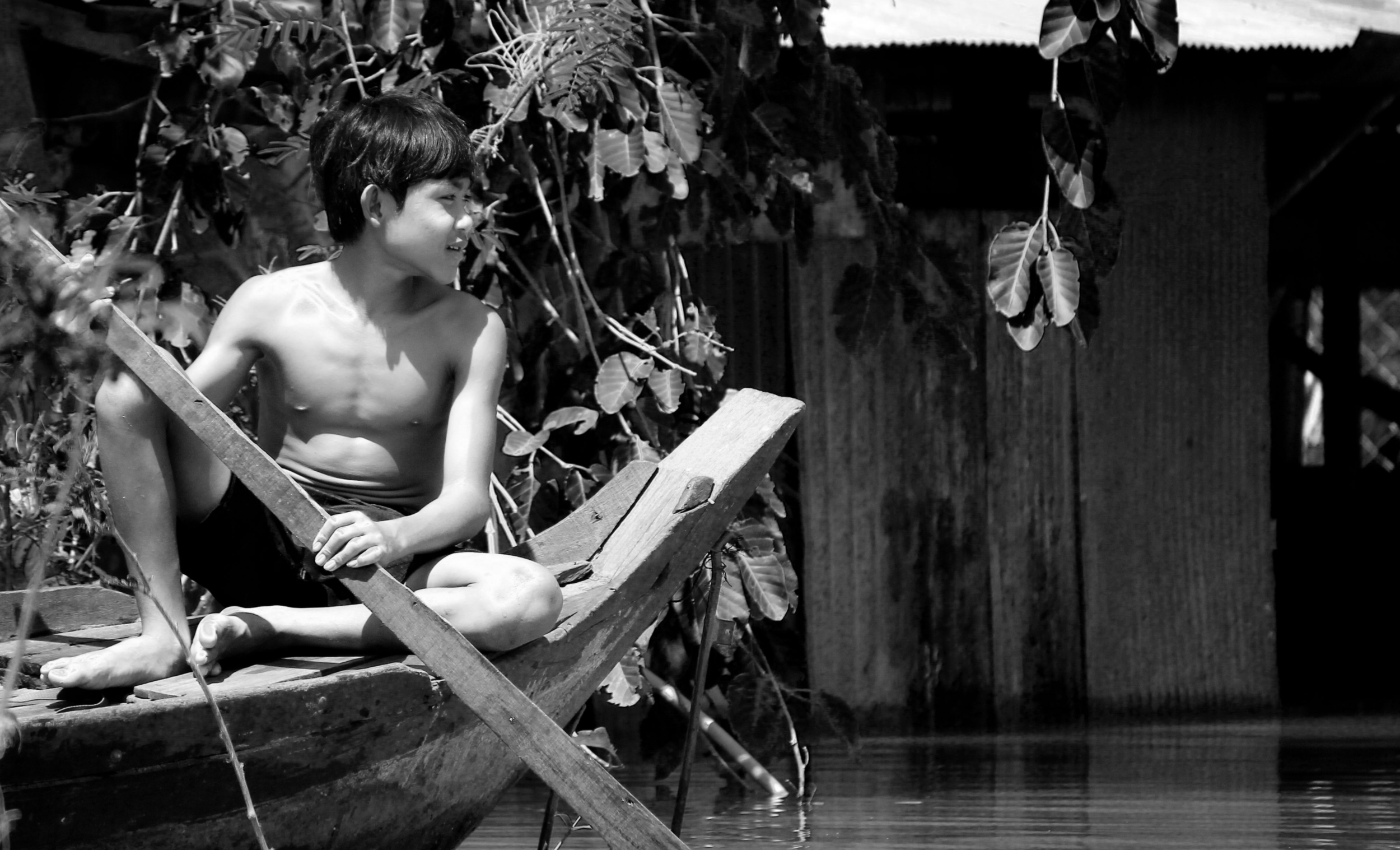

The Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror has left an indelible scar on Cambodia, and nowhere is it as clearly visible as in the lives of the country’s 5.5 million children. According to UNICEF, 38% of Cambodians are under the age of eighteen and almost half of them are malnourished and show signs of moderate to severe stunting. One in ten children dies in infancy, with many dying from diarrhea, respiratory infections, and vaccine-preventable diseases. Of those who survive past age five nearly half are engaged in child labor, producing bricks, salt, and rubber, or working in quarries and scavenging refuse. The International Labor Organization estimates the number of child domestic workers in Phnom Penh alone at 28,000. For girls the situation is even grimmer, with a third of Cambodia’s sex workers under the age of sixteen. The sale of virgin girls continue to be a serious problem, the UNHRC reports, as they are especially prized for supposed rejuvenating properties and lower HIV/AIDS risk. Such children are sold to Cambodian and foreign men (mostly Asian) for anywhere from $800 to $4,000; non-virgins may go for as little as $2 per transaction. Overall, education, health, and economic security remain elusive hopes for Cambodia’s 5.5 million children, while sickness, illiteracy, and exploitation are constant risks in a country where people struggle to survive on annual per capita income of a little over $1,000.

Three decades after the Khmer Rouge was driven from power to Cambodia’s border regions the country is struggling with few resources and severe challenges. These candid photographs show Cambodia’s children as they grow up in the enduring shadow of a national nightmare.

About the Author

Nathan William Meyer is a photojournalist, international policy writer, and educator. His images and articles have been featured in publications worldwide. As a photojournalist, Meyer has reported on government crackdowns, riots, natural disasters, tribal issues, and human rights abuses on six continents. As an international policy writer, his analytic features cover conflict minerals, civil war, human development, food security, and the NATO mission in Afghanistan. When not riding India’s dusty rails or slogging through mud in Sumatra, he can usually be found in California and is available for global assignments. http://www.nathanwilliammeyer.com